The Empty Shrine on Main Street

When the Prairie Lost Its Gods and the Machines Moved In

Drive through any county seat in Nebraska, Kansas, or Iowa and count the churches. Then count the ones that are open. In Custer County, Nebraska, there are church buildings in towns where the congregation has dropped below twenty. In some cases below ten. The buildings still stand because nobody can afford to demolish them and nobody wants to be the one who gives the order. The steeples are visible for miles across the flatland, which was the original point. They were built to be seen from a distance, to orient the traveler, to announce that here was a place where people gathered for reasons that had nothing to do with commerce or convenience. The steeples still do that work. They orient you. They announce. But what they announce, increasingly, is an absence.

Gallup recorded the number in 2020: American church membership fell below fifty percent for the first time in the history of the survey, down from seventy percent in 1999. The decline is sharpest among adults without college degrees, which means it is sharpest in exactly the communities where the church was not merely a place of worship but the organizing infrastructure of civic life. The Wednesday night supper. The vacation Bible school that doubled as summer childcare. The deacon who knew which families were behind on their heating bills and quietly arranged for the difference. The church was the social safety net before the phrase “social safety net” existed, and in rural America, where the next nearest institution might be forty miles away, the church was often the only net there was.

That net has holes in it now the size of quarter sections.

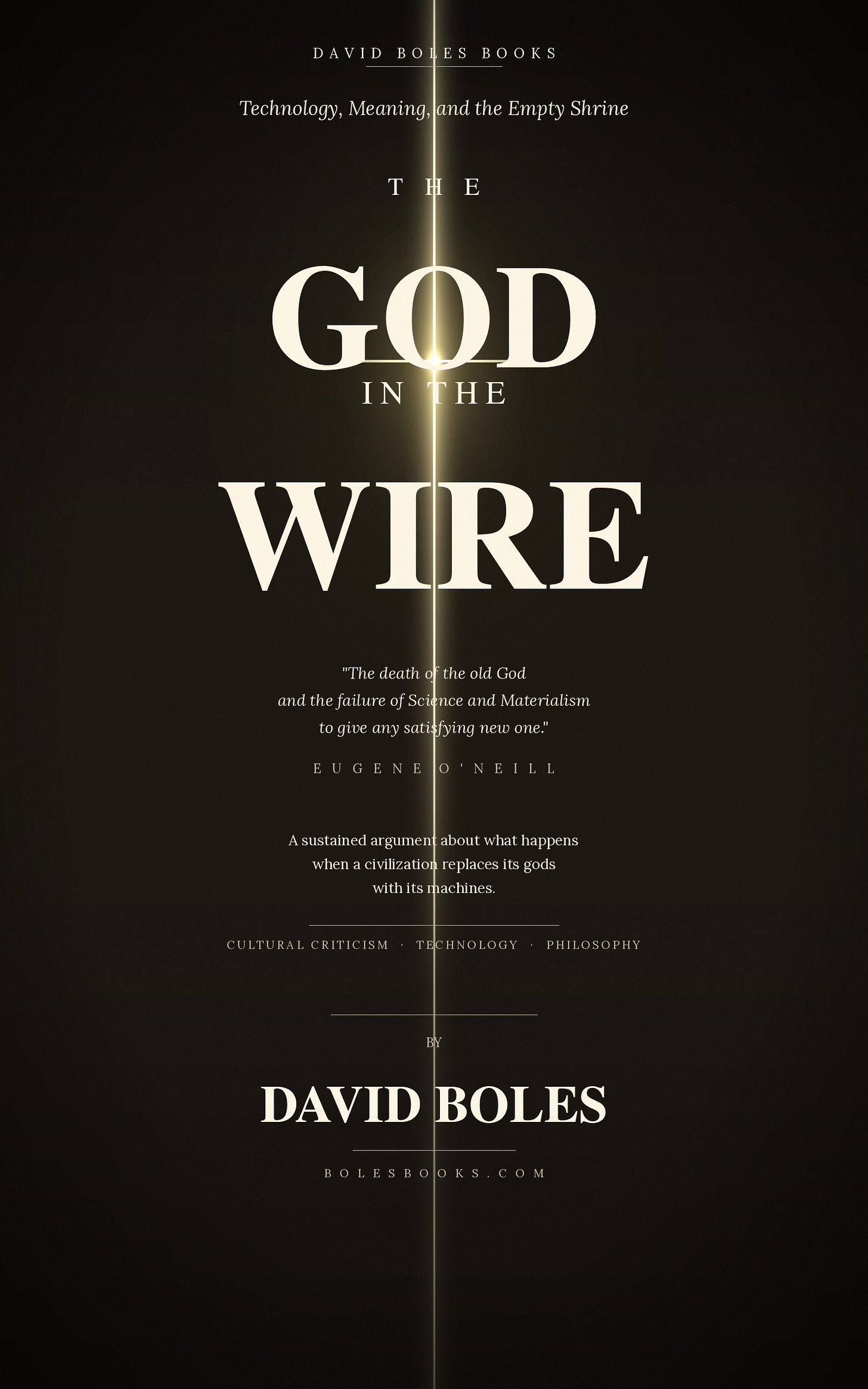

I wrote a book about this. Not about churches specifically, and not about the prairie specifically, though both appear in its pages. The book is called The God in the Wire: Technology, Meaning, and the Empty Shrine, and it is available now from David Boles Books as a Kindle ebook, a trade paperback, and a free PDF. I am mentioning it here, in Prairie Voice, because the argument the book makes has a prairie dimension that the other publications in the Boles network are not positioned to address, and it is a dimension that matters.

The book’s thesis, drawn from Eugene O’Neill’s unfinished trilogy about “the death of the old God and the failure of Science and Materialism to give any satisfying new one,” is that Western civilization has spent a century transferring its devotion from institutions of meaning to instruments of power, and that the instruments, for all their extraordinary capability, cannot do what the institutions did. The machine delivers force. It cannot deliver purpose. The dynamo generates electricity. It does not generate communion. The algorithm connects. It does not bind.

This argument plays out differently on the prairie than it does in the cities, and the difference is not sentimental. It is structural.

In a metropolitan area, when one institution of meaning collapses, others compete for the vacancy. The yoga studio replaces the church. The coworking space replaces the union hall. The online community replaces the bowling league. Robert Putnam documented the pattern in Bowling Alone twenty-five years ago, and the substitutions have only accelerated since. They are inadequate substitutions, as the book argues at length, but they are substitutions. Something fills the space, however poorly.

On the prairie, nothing fills the space. When the church in a town of four hundred closes, there is no yoga studio waiting to absorb its social function. When the last farm implement dealer shutters, the men who gathered there on winter mornings to drink bad coffee and talk about nothing in particular, which was their way of talking about everything that mattered, have nowhere else to go. The institution disappears and the function it served disappears with it, because there is no redundancy in a community that small. Every institution is load-bearing. Remove one and the structure shifts.

This is the landscape onto which the Surgeon General’s 2023 advisory on loneliness landed. The advisory compared the mortality effects of social isolation to smoking approximately fifteen cigarettes per day, drawing on meta-analytic data that has been accumulating for decades. The advisory was addressed to the nation, but its weight falls unevenly. In a city, loneliness is a condition. On the prairie, loneliness is becoming the default architecture.

Anne Case and Angus Deaton published their research on “deaths of despair” in 2015 and expanded it in a 2020 book. The term covers deaths from suicide, drug overdose, and alcoholic liver disease among working-age Americans without college degrees. The geography of those deaths maps onto the geography that Prairie Voice has been documenting since its first issue: the counties where the rendering plant is the largest employer, where the hospital has closed, where the school consolidated into a district that covers more square miles than some Eastern states. The deaths of despair are concentrated in communities where the old institutions of meaning have collapsed and nothing has replaced them except the internet connection and the prescription pad.

The God in the Wire devotes an entire chapter to this. Chapter Nine, “Deaths of Despair,” traces how the same structural pattern, arrival-dominance-disappearance, applies not only to communication technologies but to the economic and pharmaceutical systems that promised rural communities prosperity and delivered OxyContin. Purdue Pharma marketed that drug with the specific claim that its extended-release formulation made it less addictive than immediate-release opioids. They pleaded guilty to federal criminal charges in 2020. The communities they targeted have not recovered and will not recover within the lifetimes of the people currently living in them.

The book connects this to O’Neill because O’Neill understood something that the technology industry and the pharmaceutical industry share: the worship impulse does not disappear when its original object is removed. It migrates. It attaches to the next available surface. O’Neill’s character in Dynamo loses his faith in God and transfers his devotion to a hydroelectric generator. The parallel is not subtle, and O’Neill did not intend it to be subtle. The parallel is that a young man in rural Ohio in 2015 who has lost his church, his union, his bowling league, his sense of economic future, and his connection to every institution that once told him his life had structure and direction, will transfer his devotion to whatever is available. What was available, in too many cases, was a pill bottle.

The technology argument runs alongside this. Chapter Four, “From Chalk Dust to Cloud,” traces the transformation of American teaching from the chalkboard to the learning management system, and the transformation is not the story of inevitable progress that the ed-tech industry tells. It is the story of a specific human relationship, between a teacher and a room full of students, mediated first by chalk and slate and then by screen and algorithm, and what was lost in the mediation was not efficiency but presence. The one-room schoolhouse on the Nebraska prairie was a crude institution by any technological standard. It was also a place where a teacher knew every student’s family, where the curriculum was negotiated between the community’s needs and the teacher’s judgment, where education was understood as a relationship rather than a delivery system. The learning management system is more efficient. It is not more educational, and the difference between efficiency and education is the difference between a tool and a god.

Prairie Voice has been examining hidden systems since its first articles: the rendering plant network, the data centers grazing on wind power, the combine harvest circuit, the refugee processing that turned meatpacking towns into port cities, the handshake loans that once held communities together. The God in the Wire examines a hidden system that runs beneath all of these: the system of meaning-transfer by which a civilization replaces its sources of purpose with its instruments of convenience and then wonders why the convenience feels empty.

The book’s title comes from the TTY, the text telephone that gave Deaf people their first access to distance communication. The TTY is gone. The shelf that held it is empty. The sign above the shelf still points to it. That image, the sign pointing to an absence, is what I kept returning to while writing, because it is the image of every Main Street storefront with a “For Lease” sign in the window, every church with a steeple visible for twelve miles and a congregation that fits in three pews, every grain elevator standing next to a data center that employs fourteen people and serves a server farm in Virginia.

The sign above the shelf. The steeple above the prairie. They are the same gesture. They point to something that was there and is not there anymore, and the pointing is the last act of an institution that has outlived its function but not its architecture.