The Draining Prairie

Farming the Ogallala Aquifer Into Extinction

Brownie Wilson pulls his white Silverado off a dirt road outside Moscow, Kansas, mud covering everything except the Kansas Geological Survey logo stuck on the door with electrical tape. He walks through dry cornstalks to a decommissioned irrigation well, unspools a steel tape measure, and feeds it into the hole until gravity takes over. This is how we measure the dying: one well at a time, one foot at a time, watching the numbers fall.

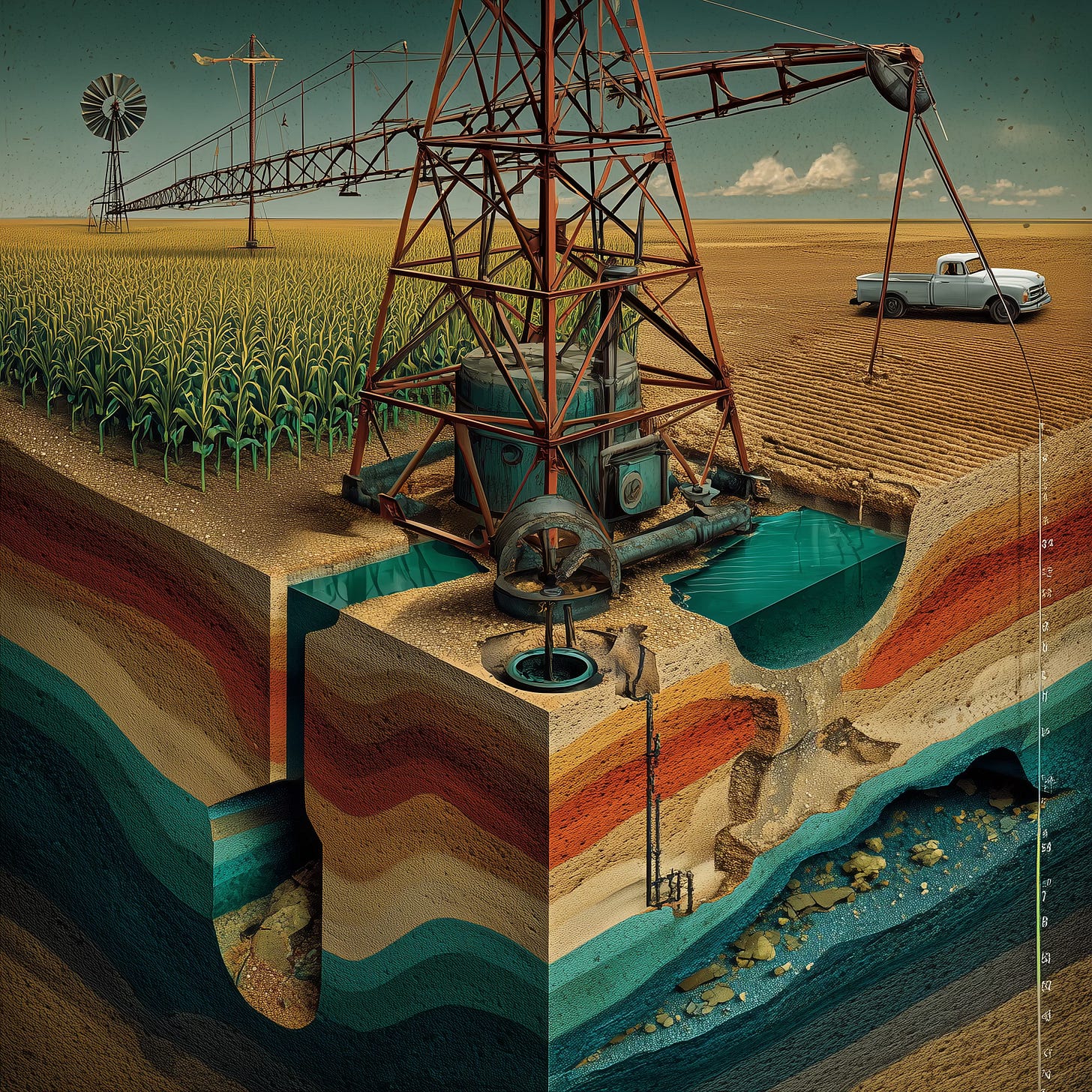

Beneath Wilson’s boots lies the Ogallala Aquifer, one of the largest freshwater accumulations on Earth, stretching 174,000 square miles across eight states from South Dakota to Texas. Geologist N.H. Darton named it in 1898 after the Nebraska town where he first mapped its extent. For thousands of years, rainfall seeped through sand and gravel deposited by ancient rivers flowing from the Rocky Mountains, collecting in underground reservoirs that held roughly three billion acre-feet of water. The Ogallala made the High Plains possible. It transformed the dust bowl into the breadbasket. It turned cattle country into corn country. And now it is running out.

The numbers are precise and catastrophic. Since the mid-twentieth century, when large-scale irrigation began with center pivot systems adapted from automotive engines, water levels in Kansas have dropped an average of 28.2 feet below their pre-pumping levels. In the Texas Panhandle, the decline reaches 44 feet. Some wells near Lubbock have fallen more than 250 feet. A 2025 University of Texas projection indicates that up to 70 percent of the Texas Panhandle will become unusable within twenty years if current pumping rates continue. In parts of western Kansas, state officials say there is not enough groundwater to last another quarter century.

Kansas Governor Laura Kelly has acknowledged the arithmetic. Some communities, she says, are just a generation away from running out of water. If they do nothing, they will suffer the consequences. The qualifier matters. If they do nothing. The problem is that doing something requires choosing between the present and the future, between this year’s crop and next generation’s survival, and nobody has figured out how to make that calculus work.

The Economics of Extraction